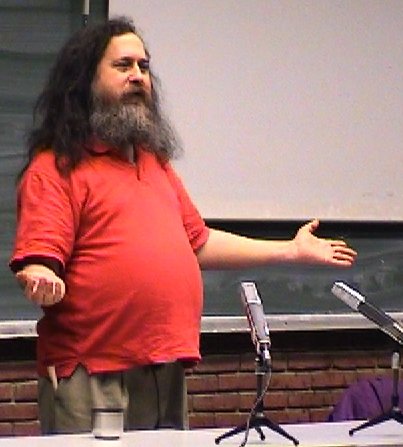

Transcript of Richard Stallman on GPLv3 in Brussels, Belgium; 1st of April 2007

Transcript released 4th of April 2007. Background and related documents:

- The wiki.fsfe.org/transcripts listing

- Side-by-side diff of v2 and v3

- Draft 3 (public comment system)

- Rationale doc

- dd3 FAQ

- The interview by Sean Daly from that day

- The 2nd draft of LGPLv3 is out

- The audio recording

Recording thanks to Sean Daly. Transcription by Ciarán O’Riordan. Please support work such as this by joining the Fellowship of FSFE, by donating to FSFE, and by encouraging others to do each. The speech was given in English.

Table of contents

- What is Free Software?

- The GNU project

- Free Software licences

- Internationalisation

- Tivoisation

- Tivoisation – the limits in draft 3

- Deflating the EUCD and DMCA

- Novell, Microsoft, and patents

- Termination

- Formalising added permissions

- BitTorrent

- Patent retaliation and the Apache licence

- The bracketed, dated clause

The Presentation

(go to menu) [Section: What is Free Software?]

In order to understand the GNU General Public License, first you have to understand what free software means. Free Software means software that respects the users’ freedom. Software that’s not free is proprietary software. Non-free software, user subjugating software, is distributed in a social system that keeps the users the divided and helpless. Divided because every user is forbidden to share the program with anyone else and helpless because the users don’t have the source code, so they can’t change it, they have no control over it, and they can’t even verify independently what it’s really doing. It may have malicious features, quite often it does, and the users may not even be able to tell what malicious features it has.

Free Software respects the users’ freedom. That’s why it’s important when we say free software, we’re talking about freedom, not price, we don’t mean gratis software. It’s not an issue of price at all, price is merely a detail. A secondary detail, not an ethical issue. To understand the term Free Software correctly, think of free speech, not free beer.

Specifically, Free Software means that the user has four essential freedoms:

- Freedom zero is the freedom to run the program as you wish.

- Freedom one is the freedom to study the source code and change it so that the program does what you wish when you run it.

- Freedom two is the freedom to help your neighbour; that is, the freedom to distribute exact copies to others, when you wish.

- Freedom three is the freedom to contribute to your community; that’s the freedom to distribute copies of your modified versions, when you wish.

Each of these freedoms is the freedom to do something if you wish, when you wish. It’s not an obligation, it’s not a requirement. You’re not required to run the program. You’re not required to study it or change it. You’re not required to distribute exact copies. And you’re not required to distribute modified versions. But, you are free to do those things, when you wish.

If this were a speech to introduce Free Software I would explain the reasons why those freedoms are essential, but in this brief introductions I will have to omit that. Suffice it to say that if a program respects these four freedoms, then the social system of its distribution and use is an ethical system. Which means that, in this regard at least, the software is ethically legitimate. But if one of these freedoms is substantially missing, then the program is proprietary software, meaning that the social system of its distribution and use is unethical and regardless of what the program does, it shouldn’t be distributed in this way.

Developing a non-free program is no contribution to society. It’s an attack on freedom and social solidarity. Such attacks ought to be discouraged, and I hope to see the day when they no longer occur. That is the goal of the free software movement; that all computer users should have these four freedoms, for all the software that they use. That subjugation of others, through the software that they run, should no longer occur.

(go to menu) [Section: The GNU project]

To bring this about, or at least start, in 1984 I began developing an operating system whose purpose was to be entirely Free Software. It’s name is GNU, which is a recursive acronym for “GNU’s Not Unix”. This system is, technically speaking, compatible with Unix, but the most important thing about it is that it is not Unix. Because Unix is proprietary software and GNU, because it’s not Unix, can be made free by us, it’s developers, and that’s the whole point – to give you an operating system that you can run without ceding your freedom to anyone.

There are now tens of millions, perhaps a hundred million users of a variant of the GNU system. Most of them don’t know that it’s a variant of the GNU system because they think it’s Linux. Linux is actually one component of the system they use. A component that does an essential job and that was developed in 1991, and liberated by its developer in 1992. The GNU system plus Linux, which is the program we call the kernel, made a complete free operating system in 1992. With the GNU plus Linux combination it became possible for the first time to use a PC compatible computer in freedom.

(go to menu) [Section: Free Software licences]

The way that Linux was liberated was by rereleasing it under the GNU General Public License. The GNU General Public License is the Free Software licence that I wrote for use in the components of the GNU system. When we wrote these components, we made them Free Software by releasing them under the GNU GPL.

But what does that mean? A program is legally considered a literary work, and it’s subject to copyright. Everything that you write is automatically copyrighted – which is somewhat of an absurd law, but that’s the way it is – and copyright law, by default, forbids copying, distribution, modification of a work. So, how can any program ever be free software? The only way is if the copyright holders put on a notice saying to the users “you have the four freedoms, because we don’t object”. That notice is a free software licence. Any notice which has that effect is a free software licence.

There are actually dozens of different free software licences but the GNU GPL is the most popular one. It’s used for about 70% of all free software packages. The main difference between the GNU GPL and most Free Software licences is that the GNU GPL is a copyleft licence.

Copyleft is a technique that I invented, a way of using copyright law to defend the freedom of other people. In order to be a free software licence, the licence has to recognise the four freedoms, if you get a program under any free software licence, you have the four freedoms. The licence gives you them. And that includes freedom number three, the freedom to distribute copies of modified versions, and freedom number two, the freedom to distribute copies without modification, but when you do that, when you distribute those copies to other people, will they have the four freedoms?

Maybe yes, maybe no, it depends how you do it. For instance, even in 1984, I could see there was a danger that you might distribute a binary of the program without providing the source code, and that would deny the subsequent recipients freedom number one. The freedom to study the source code and change it so the program does what they wish.

So if you could distribute copies without source code, people would get it from you and they wouldn’t have the four freedoms. Not all of them.

Another thing you might conceivably do is put on additional restrictions. When you distribute it, perhaps you would put on a different licence and that licence might be restrictive, it might not respect the four freedoms for other people. If you could do that, they who got the program from you would not have Free Software. Many Free Software licences permit these things, so they respect the four freedoms but they don’t defend the four freedoms. A middle man could strip off the freedom from the program and then pass on the program to you and you would get the code but you wouldn’t get freedom. You might just get a binary, or you might get a binary with a licence that says you’re not allowed to copy it. Or you might even get source code, but it would say you’re not allowed to copy it. Various things might happen which would result in your not getting Free Software.

My goal, in developing the GNU operating system, was specifically to give freedom to all computer users. If it were possible for middle men to make the software non-free – if, for instance, by changing it, that they had an excuse to make the software non-free, the goal would be defeated. We would fail to provide freedom to the users.

So I designed a Free Software licence specifically to make sure that everyone who gets any version of the program gets it as free software, with the four freedoms. In version one of the GNU GPL, which was published in 1989, it was designed to block the two kinds of attack that I just described to you.

One being: don’t distribute the source code, release only a binary. Well, GPL version one said a condition of distributing binaries was that you make source code available also, to the same people. That blocked that one attack.

The other attack was to put on additional licence terms, to change the licence. Well, GPL version one said you have permission to distribute copies but it has to be under this licence, no more and no less. Any other way, you’re not allowed to distribute. So, no adding other requirements. No removing the requirements that protect peoples’ freedom. Every copy that everyone gets, legally must be distributed under the same licence: the GNU GPL.

In 1991, I published version two of the GNU GPL, and this blocked another possible method of attacking users’ freedom. A method I didn’t know about in 1989 but which I became aware of afterward. This would be that a patent holder might sue a redistributor, and in the settlement the redistributor might agree “when we redistribute this program, we will put certain restrictions on the users”.

What could we do about that? Software patents are weapons that should not exist. They attack the freedom of computer users, they sabotage software development, they’re only good for the megacorporations. It’s the megacorporations that lobby for them, with the help of their pet government in Washington.

The fact is, in countries foolish enough to authorise software patents, a patent holder can stop the distribution of any program that implements the patented idea, and there’s nothing we can do in the licence of the program to prevent it from being suppressed in this way. Because the free software licence is just permission to use the copyright holder’s copyrighted work, it has nothing to do with somebody else’s patent.

We can’t prevent a patent holder from killing the program, but, we can hope to save the program from a fate worse than death, which is, to be made non-free, to be turned into an instrument of subjugation. Better that our software should cease to exist, at least for 20 years, the duration of a patent, than it become an instrument for subjugation. And that, I found a way to do. So in GPL version two, section seven says that if any conditions are imposed on you or you agree to any conditions that forbid you to distribute the program with all the freedoms granted by the GPL, then you can’t distribute at all.

So anyone who tries to sue or threaten you, and tries to settle this in a way that would turn the program into an instrument of subjugation, discovers that all he has achieved is to kill it. …which at least avoids the fate worse than death for the program. And in fact, this gives our community a certain measure of safety because very often the patent holder will not find it particularly advantageous to kill the program. On the other hand, if the patent could make it effectively non-free and charge people for permission to run it, that would be advantageous. So if the patent holder could inflict a fate worse than death, that would be more tempting than merely to kill it off. So we actually make it less likely that any bad thing will happen, by standing firm.

GPL version two has been used now for sixteen years. Over the years, we saw various reasons to change it. Two years ago, we decided it was time to start seriously working on this and get out a new version. We realised it would take time. I set aside several months to work on GPL version three in 2005, so as to prepare the first draft that was released in January 2006.

We have just published the third discussion draft and we’ve decided to wait for sixty days and then prepare what we hope will be the final draft for the last bit of comments before the final draft.

So what are the changes we’ve made?

People often ask for a simple summary of these changes, but there can’t be one, and the reason is that the changes are all in specifics because the basic idea is the same: defend freedom for all users. That will never change. So all the changes are in specific areas and details. Let me tell you about the most important ones. One of them is internationalisation.

(go to menu) [Section: Internationalisation]

We have changed the language to avoid certain terms whose meanings vary more than necessary between countries. Terms like “distribute”. In GPL version three, we will not use the word “distribute”. We’ve formulated two new terms, and defined them in ways that get results that are as uniform worldwide as possible. The first term is “propagate”. That means basically copying, or anything else like it, that requires permission under copyright law.

Anything except just to modify one copy or run it is to propagate the work. And then the second term is “convey”. “Convey” basically replaces “distribute to others” but it’s not defined in terms of the word “distribute”, it’s defined in terms of propagate in such a way that others may get copies. So we avoid the word “distribution”, and then, in the bulk of the licence, we set terms for propagating the work and terms for conveying the work. And this way the resulting conditions are as uniform as possible worldwide. Now, they will never be exactly uniform, as long as some details of copyright law vary.

(go to menu) [Section: Tivoisation]

Another major change consists of a new form attacking a user’s freedom that we’ve seen in the past few years. It’s called tivoisation. This is the practice of designing a machine so that if the user installs a modified version of a program, the machine refuses to run it.

It’s named after the first product I heard of which did this, which is called the Tivo. The Tivo contains Free Software released under version two, and they provide the source code, so the user of the Tivo can modify the program and compile it, and install the modified version in his machine, whereupon the machine won’t run at all because it notices that this is a modified version. This means that in some nominal sense, the user has freedom number one, but really, in practical terms it has been taken away, it has been turned into a sham. And this happens systematically, and it makes a systematic threat to users’ freedom. So we’ve decided to block this, and the way we block it is as part of the conditions for distributing binaries, we say that if you distribute in, or for use in, a certain product, then you must provide whatever the user needs in order to install her own modified version and have them function the same way, unless her changes in the code change the function. But the point is that it’s not just the user has to be able to install it and has to be able to run, but it has to be able to do the same job, despite having been modified.

If the mere fact that the program is modified is detected and prevents the program from doing the same job, that’s also a violation, that means that the installation information is insufficient, and that is what would happen under Microsoft’s scheme that it used to call Palladium. The idea was that files would be encrypted so that only a particular program could ever read them. If you got the source code of that program and you modified it and you compiled it, the checksum of your version would be different. So your version would be unable to read the files encrypted for the original version. And the original version would be unable to read any files encrypted for your version except that there aren’t any. They would pretend that this is just a symmetrical situation and they haven’t done anything to shaft you, but our conditions say they have to give you what it takes so that you can make your modified version do the same job, and the mere fact that it’s been modified may make it fail to do that job.

(go to menu) [Section: Tivoisation – the limits in draft 3]

In version three we’ve decided to limit this requirement somewhat. It’s limited to a category that we call “user products”, which include consumer products and anything that’s going to be built into a house. This is to exclude products that are made specifically for businesses and are not normally used by consumers at all.

The reason we did this is because the big danger is in the area of user products, and this way we were able to get at least a partial agreement of businesses that at least we hope will be able to help us actually put an end to this threat.

The products that do tivoisation typically do it because there is some other malicious feature in the product. For instance, the Tivo spies on the user and it implements Digital Restrictions Management. That’s why they want to stop you from changing the program. Digital Restrictions Management is unethical. It shouldn’t ever be tolerated. And spying on the user is unethical also, but we have not put anything in the GPL to say that you can’t make the software spy on the user or that it has to be able to copy things. There is no restriction at all on what functionality your modified version of the program can have.

The anti-tivoisation requirement doesn’t limit you in that regard. You can implement the nastiest features you can think of and release a modified version with those nasty features. We’re only trying to make sure that the users who get the program from you will have the freedom to remove those nasty features and fill in whatever useful features you took out. They should be free to modify it just as you were free to modify it. That’s what the anti-tivoisation provisions do.

(go to menu) [Section: Deflating the EUCD and DMCA]

We also have provisions in section three to try to defeat unjust laws such as the Digital Millennium Copyright Act in the US and the EU Copyright Directive and any similar laws that implement that WIPO copyright directive – a treaty which no government representing its citizens would ever sign.

It actually has two paragraphs. One which is aimed at the DMCA and similar laws, and another which is aimed at the EU Copyright Directive, but they both achieve the same goal. The goal they achieve is, if somebody uses GPL covered software as part of a scheme to encode or decode works, then he has waived any possibility of claiming that some other software which decodes those works is a violation of these laws. This is simply a way of trying to prevent people being forbidden to distributed software, perhaps modified versions of the same software or perhaps not but either way, we’re making sure that these laws can’t be used to suppress the modified versions that people may wish to distribute under the GPL.

[26:30]

(go to menu) [Section: Novell, Microsoft, and patents]

There’s another form of attack on Free Software’s freedoms that we found out about last November with the Novell-Microsoft deal. What happened was that Novell made a deal with Microsoft where Novell pays for distributing copies of GPL-covered software and Microsoft gives the customers of Novell a very limited patent licence which is conditional on their not exercising many of the rights that the GPL gives them.

This is a big threat, so we’ve gone at it from two directions. One is aimed at Microsoft’s role in that deal. We say: if you make a deal to procure someone else’s distribution of a program under GPL version three and you provide any sort of patent licence to anybody in connection with that, then it extends to anybody who gets it. So if Novell were to distribute software under GPL version three under this deal, then this affects Microsoft because they’re procuring distribution through this deal.

The other paragraph, and these are both in section [11], is aimed at the Novell side in the deal, which is, it says that if you distribute the program under an arrangement you made with someone else, to gain promises of patent safety for your customers in a discriminatory way, then you’re violating the licence and you lose your right to distribute.

This actually has a few more conditions because we were trying to avoid covering certain other things, for instance, consider a patent parasite, one of those companies that has only one business which is to go around threatening people with patent law suits and making them pay. When this happens, the businesses that are attacked often have no choice but to pay them off. We don’t want to put them in a position of being GPL violators as a result. So we put in a condition: “this paragraph applies only if the patent holder makes a business of distributing software”. Patent parasites don’t. As a result, the victim of the patent parasites is not put in violation by this paragraph.

We also did something to exclude blanket cross-licences and various other practices which are not threatening in the same way.

[29:38]

This section [11], which these paragraphs are included in, does somewhat more. We decided in GPL version three that distributors should explicitly give patent licences when they distribute the software. We do this in two ways. Those that contribute to the development of the program, that make any changes at all, give an affirmative patent licence to all downstream recipients. Those who just pass along copies, without changing it, they are bound not to sue any of those downstream recipients or their licence terminates.

This is a sort of compromise that is designed to encourage lots of companies to participate in the distribution, and thus, we hope, make our community somewhat safer.

In previous versions of the GPL, we didn’t have any kind of explicit patent licence. We took for granted that if you distribute someone a program under the GPL and you say that he’s allowed to do certain things, that you can’t sue him for doing those things. And in the US, that’s true, within certain bounds, but it’s not true worldwide. So this is another aspect of internationalisation – getting the same result around the World.

(go to menu) [Section: Termination]

Another change that we have made is in termination. With GPL version two, if you violate the licence, you have lost your rights to do anything with the program. And the only way to get them back is to go to all the copyright holders and beg for forgiveness. Which in most cases they will give you, if you show that you are going to follow the licence in the future, but their may be lots and lots of copyright holders.

This could be a gigantic amount of work. It could be totally unfeasible. With GPL version three, your licence is not terminated automatically. Rather, the copyright holder can write to you can say “I’m putting you on notice”, and after that point, the copyright holder can terminate your licence, if he wants to. But he doesn’t have to. He could just forgive you instead if he sees that you’re going to comply.

The result is, suppose you do something that violates the licence, and you distribute an entire GNU/Linux distribution with thousands of programs in it, and you fail to follow the requirements. And suppose ten copyright holders contact you and say you violated the licence, and you say “Oops, I better do this right” and then sixty days go by and maybe, say, five more copyright holders will contact you within those sixty days then those are the only ones that can terminate your licence. But the idea is that you show those fifteen developers that you are complying now and you promise to keep doing so. And they say “Ok, we forgive you”.

You don’t have to find all the other thousands of copyright holders and ask them for forgiveness. So, as long as you keep on with your violating practice, all the copyright holders still can put you on notice when the word gets around to them, but when you stop violating the licence, then they have sixty more days when they can still complain, and then they can’t complain anymore. So only the ones who complain within that time are the ones you have to deal with.

[34:00]

We’ve also put in an automatic cure period for first time violators. If you violate the licence, and it’s the first time you violated the licence for a certain copyright holder and you correct it within 30 days, things are automatically restored. You’re ok. But that doesn’t apply the second time.

We’re trying to make it easy for accidental violators, those who are willing to clean up their act, while still facilitating enforcement against those who don’t clean up their act.

[34:55]

Another change we’ve made, has to do… …what we’ve done that’s new in section 10 is we’ve dealt with kinds of situations that arise when a company subdivides or sells a division to another company, what happens then? We want to make sure this is clear. It shouldn’t be very controversial, but at least now it’s well defined.

(go to menu) [Section: Formalising added permissions]

Another thing that we’ve done is that we’ve formalised what it means to give added permission. There’s a practice used with GPL version two which is common enough which is that you say “This is released under version 2 of the GPL or later, and in addition we say you can do X, Y, or Z”. Added special permission as an exception.

And this is perfectly fine since what it means to release a program under a free software licence is simply you give the permission stated in the licence and you can also give other permissions.

But in order to make it clearer what this means, we’ve formalised it. So we’ve explained that you can give additional permissions for part of the code that you introduce into the GPL covered program, where you have the right to give those permission. Because the program is available under the GPL terms, when somebody modifies it, she can take off the added permissions. The GPL gives her permission to release her version under the GPL. She doesn’t have to give any added permissions for her version. But she could also pass on those added permissions because she got those added permissions to you and when she modifies those parts, she can also give those same added permissions for those changes when she wants.

So when a program is released under GPL plus added permissions, everyone who passes it along has a choice. Preserve the added permissions or remove them. Section 7 explains this. It also explains that certain kinds of explicit requirements found in other free software licences are, under our understanding, compatible with the GPL and that’s in fact our practice with GPL version two but again, it’s good to make it explicit.

And they are basically trivial ones. Like, this copyright notice can’t be removed. Or different statements of warranty disclaimers. They’re not substantive conditions.

In draft 2, this section, section 7, was more complicated. We set it up so that there were a few specific kinds of substantive requirements that you could add. And so we’d need a lot more complicated mechanism to keep track of them. A lot of people didn’t like the complexity of this. So we got rid of that and we dealt with those issues in other ways. For instance, there’s a section in the latest draft which says when a program is released under GPL version three, you can link it with code that is under the Affero GPL. In a previous draft, we said that the added requirement in the Affero GPL was one of those requirements that you could add to parts of a program that you contribute. Now, it isn’t. Now, the GPL is purely and simply the GPL and it only allows linking with other code that was released by its developers under the Affero GPL.

The Affero GPL, for those who don’t know, is basically GNU GPL version two, plus one additional requirement which says if you use the software publicly on a website, then you’ve got to give the users of the site a way to download the source code you’re running. The source code corresponding to the version they are talking through.

The basic idea is that for those developing software meant for use in this way, on servers, they want those who publicly deploy modified versions to contribute their code back to the community.

When we advised Affero on releasing this licence, we had the intention of making a future GPL version compatible with it and this is how we’re going to achieve it.

(go to menu) [Section: BitTorrent]

Another change that we’ve made is for support of things like BitTorrent. BitTorrent is peculiar because when you receive copies, you automatically end up distributing copies to other people and you don’t even know it. This is so bizarre, that I never imagined any such thing back in 1991. And in fact, distributing a program under GPL version two using BitTorrent does things that violate the GPL.

All these people are redistributing copies and they don’t know it, and they are failing to carry out their responsibilities under the GPL. So we changed it so they won’t have any problem. Obviously, distribution using BitTorrent should be OK.

[42:00]

The problem has to do with binaries. The GPL’s idea is that if you distribute binaries, you’ve got to make source available. But if somebody’s participating in a torrent for the binaries, well, he may not know where the source code is, and he didn’t set it up anyway, and we don’t want to make him responsible for dealing with the source code, as a mere user trying to get a copy through the torrent.

Another change, that will make things simpler for a lot of people, is that you will now be permitted to distribute physical copies of binaries and put the source code on a server for people to get. The reason that wasn’t allowed in the past was that for a lot of users in the past, downloading the corresponding source code might have been prohibitively slow and expensive.

In a lot of parts of the World, certainly, sixteen years ago, people wouldn’t have had broadband. All they would have had is dial-up connections. You could give somebody a CD of an entire system, and if you could say to him “to get the source code, just pull it down through your phone line”, that would have been ridiculous. So we said you have to offer them to mail them a source CD, or other source medium, which would have been a lot cheaper and much more feasible than getting the whole thing through a phone line. But nowadays in fact there are services which which download anything for you and mail it to you on a CD anywhere in the World and they don’t charge very much. So the problem we were trying to protect against, which is that lots of users would find it unfeasible to get the source, isn’t a problem anymore. These services charge less than a mail order service required by GPL version two is likely to cost. So we can just say, we presume people will use those services if they need them and we don’t have to put that requirement on every distributor.

[44:44]

I think this is basically it. There are many little details, and I certainly have forgotten about some of them right now.

We took out the paragraph in GPL version two about putting on a geographical limit saying that you can’t distribute the program in a certain country if something like patents in that country have effectively made the program non-free. We think we’ve defended against that pretty well and nobody ever used that anyway.

So, in about 90 days…

[interruption for tape change]

(go to menu) [Section: Patent retaliation and the Apache licence]

Previous drafts had a couple of provisions regarding retaliation against aggression using software patents. First of all, there was a very limited kind of retaliation directly in the GPL itself which said that if somebody started using a modified version of a program and then sued somebody else for patent infringement for making similar improvements in his own version, that this would cause termination of a specific right, namely the right to continue modifying the program.

We took that out because it didn’t seem like it would be terribly effective. We also, in section 7, where it allowed putting on additional requirements, one of them was a stronger kind of patent retaliation and there were two kinds that were allowed. The latest draft essentially does one of them itself, and so we don’t need to make that another kind of requirement you can add. And the other kind, it looked like nobody’s actually doing it, so just for simplicity we took out that option.

The reason that we allowed people to add these two kinds of patent retaliation clauses was for compatibility, and one of them is used by the Apache licence. We hoped to make GPL version three compatible with the Apache licence and we thought we had. We were focusing on the Apache licence’s patent retaliation clause, and in previous drafts we said it was ok to add that requirement to the code you contribute. Now we just have that requirement, later on in the GPL, so it doesn’t even need to be added.

So we are compatible with that clause in the Apache licence but a few months ago we noticed that there was another clause in the Apache licence requiring indemnity in certain cases, and there’s no way we can be compatible with that. So we’re not going to achieve that goal of making GPL version three compatible with the existing Apache licence. I regret that.

(go to menu) [Section: The bracketed, dated clause]

There’s one bracketed clause in the current draft and that concerns a cut-off date in the paragraph that forbids making deals to get patent safety for your customers alone. We haven’t decided whether that will apply to deals that have already been signed, or only deals that are signed after the release of this draft. And that mainly depends on how good a job we find we have done drawing a line between these pernicious deals and other kinds of deals that we don’t want to cover. We’ve come up with some criteria that seemed to do the job, and we hope to find out whether we’ve really done the job.

We think that we have addressed the specific deal between Novell and Microsoft sufficiently well with the other requirement, the one that is aimed at Microsoft’s role in that deal. Even if we post-date the effect of the second paragraph, the one that aims at the Novell role, such that it doesn’t apply to Novell, we’ve dealt with that particular deal. But if we have drawn the lines well enough, or if we can, then we’ll make it apply both to existing and to new deals. It’s a decision we haven’t made yet.

[52:00, end]

[Note: for more information on GPLv3, see FSFE’s GPLv3 page and the background and related documents linked at the top of this page]

在 IBM Bluemix 云平台上开发并部署您的下一个应用。

在 IBM Bluemix 云平台上开发并部署您的下一个应用。